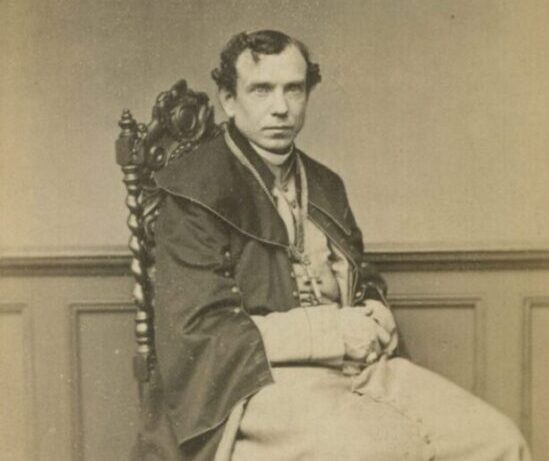

Saint Zygmunt Szczęsny Feliński around 1862 (photographed by Jan Mieczkowski)

by Tomasz Hen-Konarski

We post here a newspaper report on the 1862 ordination of Zygmunt Szczęsny (Feliks) Feliński as Archbishop of Warsaw. The piece appeared in Gazeta Polska (“Polish Gazette”), one of the leading dailies published in Warsaw in the nineteenth century. In the 1860s, the periodical was owned by Leopold Kronenberg, a successful Protestant entrepreneur of Jewish origin and a moderate conservative politician. Kronenberg hired as its literary editor Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, author of almost three hundred historical novels.

Gazeta Polska reprinted the description of Feliński’s ordination from Kurier Wileński (“Vilnius Courier”), which, in turn, had had it translated from Severnaia Pochta (“Northern Mail”), the official mouthpiece of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs. This means that the text in question has a complex nature: the readers of its Polish-language version were very well aware of its origin as a semi-official report in a government-affiliated newspaper, yet they would also see it as a logical element of Kronenberg’s cautiously patriotic profile.

From the vantage point of our research project, which explores the issue of bishops’ oaths of allegiance in East Central Europe, this text is interesting in more than one way. It describes the public ordination of a bishop, on which occasion the newly consecrated hierarch was immediately endowed with the jurisdictional authority of metropolitan, resulting in three separate oaths: first, one to the pope, then one to the emperor and his successor (each of these two oaths was taken before the rite of episcopal ordination), and then one to the pope again, followed by the conferring of the pallium. The whole ceremony in question is even more interesting, because it allows us to appreciate the complex status of the Kingdom of Poland (often referred to as Congress Poland), which in the 1860s was still treated as a separate entity from the rest of the Russian Empire.

The 1847 concordat between Russia and the Holy See did not address the issue of oaths, which meant that Rome tacitly accepted that oaths were to be regulated by the Russian laws and traditions. The account we find in Gazeta Polska shows that in this respect, Russian practices were not exceptionally onerous. For example, the bishop swore the oath to the pope before he swore the oath to the emperor. At the same time, though no member of the imperial family was present for the ceremony, the government did not fail to use the public character of the event to project its claims to patronage and control over the Catholic Church in the Russian Empire. One need merely note the role of ministers and other state officials, as well as the place where the ceremony was performed: it was held not in Saint Catherine’s Church, the main Catholic church in Saint Petersburg, but rather in Saint John’s Church, located in the Vorontsov Palace, which housed the Page Corps, a prestigious institution attached to the imperial court.

The political circumstances of this particular episcopal nomination also merit consideration. The so-called post-Sevastopol thaw and the successful unification of Italy awakened great hopes in the Kingdom of Poland, leading to a wave of patriotic demonstrations in 1860 and 1861. Throughout this period, the Russian authorities vacillated between conciliatory and violent measures, further aggravating the situation. In mid-October 1861, the government introduced martial law and violently suppressed the memorial mass in the Warsaw cathedral on the anniversary of Tadeusz Kościuszko’s death. In response, diocesan administrators (Archbishop Antoni Melchior Fijałkowski had just passed away) announced the closure of all churches and chapels in the Polish capital and its vicinity. This was a major embarrassment for the Russian government, forcing it to seek compromise.

In this situation, Zygmunt Szczęsny Feliński seemed a suitable candidate for Archbishop of Warsaw. He had impeccable patriotic credentials, as his mother had been exiled to Siberia for her involvement in the conspiracy led by Szymon Konarski, a Mazzinian emissary and a Protestant Lithuanian by birth who had been executed by the Russians in 1839 and was considered a martyr of the Polish struggle for independence. Additionally, before becoming a priest, Feliński himself had participated in the 1848 uprising in Greater Poland, albeit briefly. He was also a Catholic conservative opposed to the radicalism of the Warsaw “reds,” who were pushing for a confrontation in the Kingdom of Poland. The government circles knew him relatively well as a reliable professor at the Imperial Roman Catholic Theological Academy in Saint Petersburg and an effective manager of his charity for orphans. They had good reason to hope that he would help them cool down the situation in Warsaw, although it was also clear that he was not a careerist who would be willing to serve as their unconditionally obedient tool. In any case, the emperor himself interviewed Feliński in private the day before his ordination, and the outcome was positive.

Finally, a few words on the English-language text offered below. We render all personal names as they appear in the text, while giving the place names in the official language of the states to which they belong today, hence Mahiliou instead of Mohylew or Mogilev. Translations are the product of interpretation, approximation, and simplification, and thus often lead to distortion of meaning. We had to make some difficult choices, none of which was completely arbitrary. One example will suffice here: we have chosen to use the English verb “consecrate” to preserve the connotations and tone of the Polish verb “wyświęcać,” although “ordain” could be more accurate. The translation below is not scholarly sensu stricto. Its essential function here is to disseminate knowledge about our project and nurture interest in our field. For academic purposes, we encourage our readers to consult the original Polish-language version in two issues of Gazeta Polska that appeared in Warsaw in mid-February 1862: [1] [2]

A design of the Maltese Chapel (Saint John’s Church) by its architect Giacomo Quarenghi

[…]

It was announced in the eleventh issue of Poczta Północna that on Sunday, 14 January, Father Feliks Feliński would be ordained in the local church of Saint John of Jerusalem [in Saint Petersburg] to embrace the dignity of archbishop of Warsaw and receive the pallium sent for this purpose from Rome. We will try to give our readers a description of this solemn rite.

The consecration of Father Feliński attracted large crowds. Those present included messrs. Minister of Internal Affairs [Petr Valuev], Minister Secretary of State of the Kingdom of Poland [Józef Tymowski], his associate Privy Councilor Platonov, Minister of the Treasury [Aleksandr Kniazhevich], member of the Council of State of the Kingdom of Poland Margrave Wielopolski, Grand Master of Ceremonies of the Kingdom of Poland Count Borch, Director of the Department for Foreign Confessions Count Sievers, ambassadors of Spain and England, envoys of Austria, Belgium, Bavaria, and others members of the diplomatic corps, as well as some gentleladies from the local high society.

Around 11:00 AM, His Eminence [sic] Archbishop of Mahiliou, metropolitan of all Roman Catholic churches in the Empire Father Wacław Żyliński; the newly elected archbishop; three assisting bishops; and other clergymen entered the church. After reading a short prayer at the altar, the metropolitan sat on the throne (to the left of the altar), whereas the new elect together with the three assisting bishops entered a separate chapel, where he dressed in the priestly vestments.

When everything concerning the service had been prepared, the metropolitan rose from the throne, approached the altar, and sat at the assigned place in front of it, facing the people. Assisting bishops brought the new elect to the metropolitan, before whom he bowed his head, having previously taken off the red cap called biretta; then, the assisting bishops, in full episcopal garb, covered the head of the new elect with their mitres. After this, all four of them sat opposite the metropolitan at some distance: the new elect right in front of him, the older assisting bishop Count Father Plater to the right of Father Feliński, the two younger ones, Father Staniewski and Father Bereśniewicz, to the left.

After a few minutes, they rose with their heads uncovered. The older one among the assisting bishops turned to the metropolitan and asked him in the name of our Holy Mother the Church to invest the present priest with dignity.

“Do you have apostolic permission for this?”

“We do.”

“May it be read aloud,” the metropolitan replied.

They then read aloud the papal bulls concerning the consecrated and his consecrator. Father Szczygielski, a member of the Warsaw cathedral chapter, read them in Latin.

When the reading was over, the new elect approached the metropolitan, knelt before him, and took the customary oath on the Gospel to the Holy Father and the Apostolic See. The metropolitan held the Gospel in front of the consecrated, who touched it with his both hands. After this, the metropolitan and the consecrated rose, and the latter took an oath of allegiance to the EMPEROR and the EMPEROR’S SON, Heir to the Throne. During this act, the Minister of Internal Affairs and the Minister Secretary of State of the Kingdom of Poland came closer to him.

Subsequently, the new elect and the assisting bishops took their seats again. Then, started the examination of the consecrated: the metropolitan asked questions concerning the creed, the teaching of the people, submission to the Roman Catholic Church, the purity of mores, etc. After each question, Father Feliński rose and gave short answers:

“I wish, I believe, I agree,” and other appropriate replies to the questions posed.

The consecrator closed the examination by saying:

“May God Almighty strengthen your faith, my Beloved brother in Christ, for your true and eternal benefit.”

All responded:

“Amen.”

When the examination was over, the three assisting bishops led Father Feliński to the metropolitan. Father Feliński knelt and kissed the metropolitan’s hand. The latter took off his mitre, turned to the altar, and started the Holy Mass (introitus), with the consecrated to his left. Assisting bishops with their chaplains did alike. Then, the consecrator came to the altar, kissed it and the holy Gospel, waved incense over the altar, and sat on the throne, while the assisting bishops took the new elect to a small chapel, where he dressed in new vestments. There, standing at the altar with his head uncovered among the assisting bishops, he started a low mass, which he said at the same time as the metropolitan celebrated the solemn mass at the main altar. Meanwhile, the metropolitan sat again in front of the altar and the assisting bishops brought to him the consecrated, who, his head uncovered, bowed with reverence to the consecrator. The assisting bishops did the same, but without taking off their mitres. Then, they took their seats.

The consecrator, his mitre on his head, turned to the consecrated and listed in a succinct manner all the duties of the episcopal dignity, and when everybody had risen, he exhorted those present to lift their prayers to God, asking for His grace for the new elect.

Then, a litany began. The metropolitan and the assisting bishops knelt in their mitres, while the new elect prostrated to the left of the metropolitan. The entire clergy and all those present knelt. After the litany, the consecrator, crosier in hand, rose, turned to the consecrated, and thrice asked God for a blessing for him, then thrice made the sign of the cross upon him. The assisting bishops did the same but without rising, still kneeling. After this, the consecrated knelt again and the litany was continued. When it was finished, all rose, the metropolitan, his mitre on his head, took his seat in front of the altar, and the consecrated knelt before him. The metropolitan took the Gospel passed to him and put it, open, on the head and back of the consecrated, after which the metropolitan and the assisting bishops laid their hands on the head of the consecrated and said:

“Receive the Holy Spirit.” Then, the metropolitan rose from his seat, took off the mitre, and besought God to pour His blessing on the newly consecrated. After this, he lifted his hands and said:

“Unto the ages of ages,” to which the clergy responded:

“Amen.”

“The Lord be with you.”

“And with your spirit.”

“Lift up your hearts.”

“We lift them up unto the Lord.”

“Let us give thanks to the Lord.”

“It is right and just.”

Then, the prayer began:

“Vere dignum et justum est,” (preface) during which the rite of anointment with chrism began (consecratio).

The head of the consecrated was enfolded with a white cloth, while the metropolitan knelt before the altar intoning the hymn “Veni Creator Spiritus” (Come, Holy Ghost, Creator Blest), which the assisting bishops finished.

After the intonation, the metropolitan sat on his throne in front of the altar, put on his mitre, and took off his ring and gloves. Then, his finger soaked in chrism, he twice made the sign of the cross on the head of the consecrated, who was kneeling, and uttered the following words:

“May your head be anointed and sanctified with the heavenly blessing to embrace the archepiscopal dignity.”

Having made the sign of the cross on the head of the consecrated for the third time, the metropolitan said:

“In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit,” to which the clergy responded:

“Amen.”

“Peace be with you,” the metropolitan continued, gently wiping his finger with the soft crumb of bread. When they had finished singing the hymn, he rose, took off his mitre, and recited a prayer starting with the words: “Hoc, Domine, copiose in caput ejus influat” (May this, O Lord, flow abundantly on his head), etc. Then, they said another prayer, sang an antiphon “Unguentum in capite,” and an excerpt from Psalm 132. During the antiphon, the neck of the consecrated was dressed in a long cloth. The consecrator took his seat again, put on his mitre, and anointed with the same chrism the hands of the consecrated, who was kneeling before him. Then, he made the sign of the cross upon him, saying the prayer starting with the words, “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit” and another one, “Deus et Pater.” The consecrated stood with his hands together, covered with the cloth hanging from his neck. The metropolitan, in turn, risen without the mitre, blessed a crosier and said a prayer appropriate to such occasions. Having sprinkled it with the holy water, he gave it to the consecrated, uttering the following words:

“Receive the grace of pastoral service, be piously severe in rectifying transgressions, pass judgements without ire, etc.’”

Having done this and taken off his mitre, the metropolitan rose and blessed a ring by saying an appropriate prayer and sprinkling it with the holy water. He put it on the finger of the consecrated, explaining that it is a symbol of the need to defend the Holy Church as the Lord’s Bride. Next, the consecrator took the Gospel that was kept on the head of the consecrated and gave this holy book to the latter, telling him in a few words to spread the Word of God among the flock entrusted to him. Finally, the consecrator and the assisting bishops kissed the face of the consecrated, saying:

“Peace be with you,” to which he responded to each of them:

“And with your spirit.”

After this, the consecrated went to his chapel, where his head was wiped with bread and a clean towel, his hair was combed, and his hands were washed, which was performed by the metropolitan.

[…]

A design of the altar in the Maltese Chapel (Saint John’s Church) by its architect Giacomo Quarenghi

Then, the consecrator and the consecrator continued celebrating the Holy Mass which they had started.

After the elevation, the metropolitan sat on his throne, while the consecrated left his chapel accompanied by the assisting bishops and knelt before the consecrator to kiss his hand and to give him two lighted candles, two loaves of bread, and two barrels of wine. Higher lay dignitaries of Roman Catholic confession took candles, loaves, and barrels to the altar. Loaves and barrels of wine were silvered and gilded. In turn, the metropolitan washed his hands and went to the altar. The consecrated stood by his side surrounded by the assisting bishops, the missal in front of him. Here, the offertory of bread and wine took place, during which the consecrator and the consecrated said in low voices the prayers prescribed by the Church, after which the consecrated moved to the right of the metropolitan, who said:

“Peace be with you,” to which the consecrated replied:

“And with your spirit.”

The same words were exchanged between the newly consecrated arch-shepherd and the assisting bishops. Then, the metropolitan himself took communion and gave communion to the consecrated, and they continued celebrating the Holy Mass together.

Afterwards, the metropolitan made the sign of the cross upon those present and took his seat in front of the altar, while the consecrated knelt before him. The metropolitan rose, blessed a mitre for the consecrated, sprinkled it with the holy water, and put it on his head, saying a prayer appropriate for such occasions. Then, risen again, the metropolitan took the right hand of the consecrated and, together with the oldest assisting bishop, who held the left hand of the consecrated, seated him on the same place in front of the altar, which he himself had occupied. All the while, the consecrated was holding the crosier. Finally, the metropolitan turned to the altar, took off his mitre, and intoned the hymn “We praise Thee, O God,” which the surrounding clergy continued singing.

At the beginning of the hymn, the assisting bishops led the new arch-shepherd around the church, where he blessed the people. While the singing of “We praise Thee, O God” did not cease, the consecrated took the seat in front of the altar and the assisting bishops stood at the side of the metropolitan. When the hymn was over, the metropolitan intoned an antiphon. Then, the consecrated, mitre on his head, crosier in hand, rose from his place and went to the altar, made the sign of the holy cross, first on his chest, then on his forehead, lifted his hands, and turned to bless the people. Meanwhile, the metropolitan, mitre on his head, surrounded by bishops and other assistants, stood by the altar. The consecrated knelt thrice before the metropolitan and sang “Plurimos annos.” For the last time, the metropolitan lifted him and gave him the kiss of peace. The assisting bishops did the same thing. As a matter of fact, this was the end of the rite of consecration to episcopal dignity. Yet, there was one other rite to be completed, the conferring of the pallium, which the pope customarily grants to archbishops and metropolitans.

Before being vested with the pallium, the consecrated has no right to call himself archbishop or patriarch, he cannot ordain bishops, convene synods, prepare the chrism, or consecrate churches or clerics. The pallium is a three-fingers-broad woolen band adorned with three black silken crosses, its ends also made of black silk. It is put on in such a way that one end rests on the chest, the other on the back. Before being sent to a patriarch or archbishop, it is put on Saint Peter’s grave, where it is consecrated.

The rite of investiture was the following: the pallium was brought on a cushion and put on the altar. The metropolitan sat on his throne in front of the altar, while the newly consecrated in full liturgical vestment, except for the mitre and gloves, knelt before the metropolitan and in front of an open Gospel swore an oath of fidelity to the pope, in accordance with the formula prescribed by the Roman Church. After the oath, the metropolitan rose from his place, took the pallium from the altar, and put it on the neck of the new archbishop. This rite concluded, the metropolitan sang a prayer for the health of the EMPEROR and the whole Most Illustrious House.

This is what the archepiscopal consecration of His Excellency Father Feliński looked like, followed by his investiture in the pallium. It was a solemn and truly moving celebration. Music, chants, altar decorations, magnificent vestments, and contrite prayers of the clergy: all this leaves a strong impression. We deeply regret that the limits of this article do not allow us to quote all the prayers used in this celebration, as all of them breathe with lofty thoughts and deep feeling. To give you the full idea of the celebration of the consecration, one would have to explain every gesture and every word, because they have a deep symbolic meaning.

[…]